The Illusion of Perfection

Each morning, half-awake, I scroll through my phone and am greeted by a curated gallery of faces—friends, acquaintances, strangers—all seemingly flawless and happy. Teens are already getting lip filler, Botox, buccal fat removal. No one really talks about it, but it’s obvious. Faces change silently, subtly: a jawline more angular, skin too smooth to be natural.

It’s oddly soothing to look at—predictable, polished—but also unsettling. There’s a pressure humming beneath the surface, a sense that the standards are shifting. And beneath the filters and soft lighting, there’s the quiet recognition that what we’re seeing isn’t real—not entirely.

This sentiment echoed more loudly as I thought about Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Published in 1890, the novel follows Dorian, a young man whose painted portrait ages and decays in his place. After making a wish that the painting would bear the marks of age and sin, Dorian is granted a supernatural gift. It allows him to remain outwardly perfect while his portrait absorbs the consequences of his actions.. As he plunges into hedonism and cruelty, the image becomes a grotesque mirror of his soul—a secret he hides in his attic.

Wilde’s novel anticipates the anxieties of our digital age: the obsession with youth and beauty, the careful construction of public personas, and the psychological cost of chasing pleasure while masking truth. Dorian’s story isn’t simply about vanity. It’s about the danger of confusing surface with substance, the burden of secrets, and what happens when the self we show the world no longer reflects who we are. Wilde leaves us with urgent questions—about accountability, identity, and the cost of endless self-curation.

The Cult of Youth and Beauty

Dorian Gray enters the novel as the embodiment of youthful beauty—naïve, admired, untouched by the world. When artist Basil Hallward paints his portrait, he captures not just Dorian’s appearance, but his idealized essence: flawless, eternal. Around the same time, Lord Henry Wotton begins to influence Dorian with a seductive worldview—one that worships beauty, dismisses morality, and prizes pleasure above all else.

Caught between Basil’s admiration and Lord Henry’s cynicism, Dorian becomes painfully aware of his own physical perfection. For the first time, he realizes it will fade. That awareness curdles into fear. In a moment of desperate longing, he wishes aloud that the portrait would age in his place, allowing him to remain forever young.

It seems like a passing comment, but it becomes the hinge of the novel. The wish is granted. From that point on, Dorian's life veers off course. What begins as a desire to preserve beauty spirals into a deeper detachment from consequence, accountability, and the self.

His fear of aging and fixation on beauty feel startlingly familiar. Today, youth isn’t just valued—it’s commodified. Entire industries promise to pause time: laser resurfacing, collagen supplements, and thread lifts. These aren’t fringe pursuits anymore. I know people my age getting preventative injections, tweaking their bodies before a single wrinkle appears. Like Dorian, we’ve grown wary of imperfection. We seek permanence in a world where everything, including ourselves, is supposed to change.

Wilde captured something deeply human: the desire to freeze our best selves in time. But the cultural appetite for youth has exploded. Social media platforms prioritize aesthetics; filters blur imperfections, widen eyes, and polish the face into submission. Apps let us erase blemishes, reshape our faces, and fabricate a perpetual adolescence. And the feedback loop of likes and comments only intensifies the desire to keep up the illusion.

And as the novel continues, Dorian’s descent into vanity and detachment is driven by the belief that appearance determines worth. The portrait becomes a kind of diary, recording sins he refuses to acknowledge.

He keeps it hidden, even from himself—a secret too damning to face. But that concealment isn’t unique to him.

In our world, the curated Instagram grid or the Facetuned selfie becomes a similar surface, polished to protect us from exposure. The cost, as Wilde shows, is a dangerous split between who we are and who we pretend to be.

As the novel progresses, Dorian never has to reckon with his flaws because his body shows no signs of damage. He walks through life untarnished, admired, and envied, even as his inner world rots.

But the lie wears on him. The longer he lives behind a mask, the more hollow he becomes. When beauty becomes our highest ideal, we trade self-awareness for self-preservation. Dorian doesn’t just fear age—he fears being truly seen.

The first real consequence of this detachment comes with Sibyl Vane, a young actress who falls in love with Dorian. Enchanted by her beauty and talent, Dorian sees her as an extension of his aesthetic world. But when her acting falters—because she’s overwhelmed by love and no longer performing—he is repulsed.

He abandons her cruelly, and she kills herself. It’s a moment that should break him, but instead, it triggers his transformation.

Rather than confront the weight of what he’s done, Dorian turns away. And when he sees the portrait subtly change for the first time—its expression colder, more cruel—he chooses denial over guilt. From here on, the illusion matters more than the cost of maintaining it.

Moral Decay and the Double Life

As Dorian spirals deeper into indulgence, his portrait morphs into a grotesque catalog of his sins. The picture, once admired as a masterpiece, becomes unrecognizable. Each misdeed, each betrayal, each cruel thrill leaves a visible mark: the death of Sibyl Vane after he abandons her, the blackmail and eventual suicide of a man, Alan Campbell, and the trail of scandal that follows him through society. Yet Dorian remains youthful, unscarred—a living illusion.

The split between surface and substance haunts the novel and defines his unraveling. Wilde presents the portrait as both mirror and conscience. Dorian locks it away, but he can’t escape it. He visits it compulsively, watching the lines deepen, the mouth curl into a sneer, the eyes darken with malice. The painting doesn’t just reflect corruption—it becomes it. It records what he refuses to confront, holding the guilt he won’t acknowledge, even as it dictates his every move.

And this double existence—the outward mask and hidden decay—feels familiar. We curate digital identities with the same obsessive precision: highlight reels, celebrations, carefully cropped lives. We omit the grief, the mistakes, the moral failures. Like Dorian, we sometimes believe the image is all that matters. But beneath the polish, there’s always a more complicated truth—and the gap between the two can quietly erode us.

The psychological toll builds slowly. Performing a self that contradicts private reality wears down the boundary between who we are and who we pretend to be. Anxiety, alienation, even self-loathing creep in. Dorian’s detachment grows into paranoia. He fears exposure, isolates himself, and lashes out at those who try to reach him. The illusion he worked so hard to maintain becomes a cage, and the longer he avoids the truth, the more grotesque it becomes.

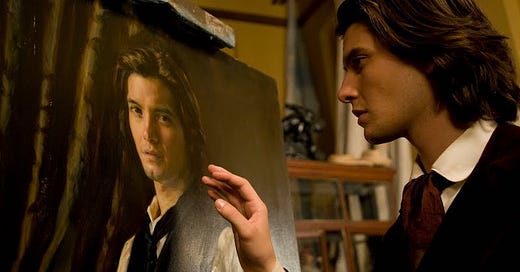

Image: Ben Barnes as Dorian Gray in the 2009 film adaptation. This moment—when Dorian first sees the portrait that will carry the burden of his soul—captures the eerie seduction at the heart of Wilde’s novel.

Influence and Corruption

But Dorian didn’t fall into this illusion alone. From the beginning, Lord Henry Wotton—witty and magnetic—planted the seed. He doesn’t force Dorian to change; he seduces him into it.

Wotton’s worldview is charming, liberated, even intoxicating: pursue pleasure, question morality, never apologize. He speaks with such wit and certainty that his cynicism feels like wisdom.

Dorian is drawn to Lord Henry’s philosophy because it absolves him of responsibility. Why shouldn’t he chase every desire? Why bother with guilt if the world only sees beauty? Lord Henry offers permission, not pressure—and that’s what makes him dangerous. He doesn’t argue, he insinuates. And once his ideas take root in Dorian, they flourish unchecked.

Today’s landscape is filled with figures who echo Lord Henry: influencers, commentators, even peers who peddle curated versions of life that celebrate consumption and detachment. Their messages are often seductive, wrapped in aesthetics and the language of empowerment. But like Lord Henry, they rarely reckon with consequences. Their ideals can take root quickly in impressionable minds, spreading in the form of aspiration or envy.

One of Lord Henry’s most dangerous gifts to Dorian is a mysterious “yellow book”—a fancy French novel that becomes his moral compass, or rather, his escape route. Dorian reads it obsessively, modeling his life after its unnamed protagonist: a man who devotes himself entirely to beauty, sensation, and aesthetic experience.

The book seduces Dorian into a life without restraint or consequence. And that’s what makes it so corrosive. It crystallizes Lord Henry’s worldview into narrative form, wrapping nihilism in poetic style and giving Dorian a script to follow.

As Dorian follows its philosophy, his life begins to mirror the novel’s: empty pleasures, destructive indulgences, and an ever-growing detachment from morality. Wilde never names the book, but its presence shows how art—like influence—can quietly radicalize, especially when it flatters our worst instincts. It becomes a blueprint for the life Dorian builds: one of surface without substance, pleasure without pause, beauty without soul.

Wilde warns us to be wary of the voices we let shape us. Dorian parrots Lord Henry’s aphorisms as if they were his own, losing track of what he truly believes. He begins to live not by reflection but by imitation, following the yellow book’s example more faithfully than any moral guide.

When Basil questions his choices, Dorian offers borrowed philosophies. He’s no longer a person with convictions—he’s a vessel for someone else’s worldview. The danger isn’t just influence—it’s the erosion of discernment, the gradual replacement of belief with performance.

And influence is never neutral. Wilde dramatizes how charismatic people can implant values in others that corrode moral clarity. After Lord Henry’s ideas begin to take root in Dorian, Basil—his friend and the man who painted his portrait—pleads with Lord Henry to leave Dorian alone, sensing the danger ahead. But it’s too late. The damage is already in motion.

Dorian grows enthralled—not just by Henry’s philosophies, but by the yellow book and the lifestyle it condones. And once captivated, he cannot unlearn what he’s absorbed. Wilde’s warning isn’t confined to his era. This kind of corruption isn’t loud—it’s ambient. It reshapes us without our knowing.

Today, the same dynamics operate not only through individuals but through algorithms. The platforms we use are engineered to reward impulse, to serve us seductive content, to collapse discernment in favor of engagement.

And as the novel continues, Dorian’s relationships with both Lord Henry and Basil evolve in telling ways. He begins as Basil’s muse and Lord Henry’s protégé—admired and shaped by both. But as he grows more detached and powerful, he no longer seeks guidance. He imitates Lord Henry’s cynicism while shedding Basil’s ideals entirely. The man who once inspired art becomes its destroyer.

Eventually, that transformation turns violent. But the clearest rupture comes when Basil—still clinging to the belief that there is goodness left in Dorian—demands to see the portrait. When Dorian finally shows him, and the truth is exposed, he kills him.

It’s a horrific moment not just because of the murder, but because of what it signifies: Dorian is willing to destroy the last person who knew his soul in order to protect the illusion. Basil had once served as a moral anchor, an artistic conscience. By killing him, Dorian severs the final thread tying him to his former self.

The Price of Hedonism

At the heart of The Picture of Dorian Gray is the question of what pleasure is worth when it has no boundaries. Dorian takes Lord Henry’s advice to its extreme, indulging in every sensation, every thrill, every taboo. Over the years, he becomes a shadowy figure in London society—whispers follow him wherever he goes. Friends vanish from his circle. Scandals attach themselves to his name like smoke. Those closest to him—artists, lovers, admirers—end up ruined, dead, or estranged. And yet, he remains untouched, ageless. A ghost with a beautiful face.

Pleasure, Wilde suggests, becomes hollow when pursued without connection or meaning. Dorian chases novelty, not joy. Each experience dulls faster than the last. His indulgence becomes addiction, not freedom. The more he seeks to feel alive, the more numb he becomes.

We see echoes of this everywhere—in the endless scroll, the dopamine hits of validation, the pressure to experience more, own more, be more. But the more we consume, the more elusive contentment feels. Wilde understood this long before Instagram or TikTok: when we make gratification our goal, we often end up lonelier, not freer.

Dorian’s tragedy is that he never stops to ask why he desires what he does. His pleasure-seeking isn’t liberating—it’s escapism. He numbs the unease growing inside him until it’s too big to ignore. Wilde isn’t condemning pleasure itself, but reminding us that untethered pleasure tends to leave a vacuum. It cannot substitute for reflection, intimacy, or moral reckoning.

Perhaps most relevant today is how Dorian’s lifestyle distances him from meaning. He doesn’t build lasting relationships; he uses people as props in his quest for sensation. His world becomes increasingly hollow. As the years go on, he finds himself haunted not just by the portrait, but by a growing sense that he has wasted something essential.

Image: I saw this live and it was great. The Picture of Dorian Gray on Broadway, adapted and performed by Sarah Snook, turns Wilde’s story into a multimedia fever dream. Every character played by one actor, fractured across a wall of screens.

Facing the Portrait

In the novel’s final scene, Dorian stands before the painting and sees what he has become. Desperate, he tries to destroy it. He stabs the canvas with the same knife he once used to kill Basil, the man who painted it. When the servants burst in, they find a withered, lifeless old man on the floor—and the portrait restored to its original beauty.

It’s one of the most haunting endings in literature. Dorian cannot destroy the truth without destroying himself. Years of denial, of masking his reality behind a perfect face, have only made the truth more grotesque—more powerful. The final image is brutal: the mask collapses, and what’s left is a stranger.

But this isn’t just a story about one man’s downfall. It’s about the quiet danger of self-deception. About what happens when we invest so fully in who we appear to be that we forget to ask who we are. It’s about the cost of never looking in the mirror—really looking—and the fear that if we did, we might not like what we see.

What parts of ourselves are we hiding? What versions of our lives are we editing into existence—and why? Who benefits from our obsession with beauty, with polish, with performance—and what do we lose in return?

Wilde’s novel compels us to confront what we’ve tucked out of sight: the insecurities, the guilt, the doubt. The aspects of ourselves we’d rather keep out of frame. And it shows how avoidance compounds over time. The longer we delay reckoning, the heavier it grows. The price isn’t just personal—it’s cultural. A society that prizes appearance over substance produces people who feel hollow even when they appear perfect.

Beauty fades, influence seduces, and unchecked pleasure distorts the soul. But most dangerously, Wilde suggests, the self begins to fracture when it’s split too long between surface and substance.

The novel doesn’t offer instructions for how to live honestly—but it insists that without honesty, we risk becoming strangers to ourselves. Dorian tries to destroy the mirror rather than face it. But the truth, once hidden, only deepens. And when he finally confronts it, he can’t survive what he sees.

Wilde doesn’t hand us answers. He hands us a mirror. The question is whether we’re willing to look—and what it might cost if we don’t.