The other night, I was scrolling through the New York Times’ list of the 100 best movies of the 21st century—half out of curiosity, half as a way to avoid doing anything meaningful—when I saw Spirited Away sitting there at number nine. It stopped me for a second. Not because it didn’t deserve the spot—of course it did—but because I couldn’t remember the last time I’d thought about that movie.

I first saw Spirited Away when I was a kid—sometime in middle school—and, like most people my age, I probably didn’t understand half of it. It was strange and eerie and beautiful in a way I couldn’t explain back then. But watching it again now—older, midway through college, halfway out the door of whatever version of my life this is—it felt different. It didn’t feel like a fantasy anymore. It felt familiar.

If you’ve never seen it—or if, like me, reading the title only half-jogged your memory—Spirited Away follows a young girl named Chihiro who finds herself trapped in a strange, dreamlike spirit world after her family takes a wrong turn on the way to their new home. They stumble across what looks like an abandoned amusement park: faded storefronts, empty streets, a leftover echo of something that used to be alive.

Her parents, lured by the smell of fresh food left out in one of the stalls, gorge themselves on what isn’t theirs—a quiet Adam and Eve moment, a bite that tips the world off balance. When Chihiro comes back, they’ve turned into pigs, devouring the plates in front of them. By then, the sun has set. The road home has vanished. And the world around her has quietly, completely altered.

Chihiro returns to her parents, as pigs.

To survive, Chihiro takes a job in a sprawling, otherworldly bathhouse that caters to spirits and gods. It’s a place full of impossible creatures, old magic, and quiet threats. The rules make no sense. The people she meets can’t all be trusted. Even her name—her only real anchor—starts to slip away when she’s forced to change her name.

In that world, forgetting your name means forgetting who you are, and the longer you stay, the easier it is to lose yourself entirely, as you become someone new after being retitled. She doesn’t get to choose when she crosses into this new version of her life. It just happens. And by the time she realizes it, she’s already in it.

The thing Spirited Away gets right—better than almost any other movie—is that the biggest transitions in life don’t happen with some grand, sweeping announcement. There’s no line you cross that tells you: you’re here now, you’ve changed. It happens quietly. You look up one day and you’re already on the other side.

Chihiro, looking up at the bathhouse.

I’ve felt it a few times over the past few years. Moving away for college. Coming back. Walking through a city that used to feel unfamiliar, and realizing I don’t register the street names anymore. And it’s not just the place—it’s the people I’m walking through it with. The way we experience it together has shifted: familiar streets, familiar faces, but somehow the dynamics have rearranged. It’s new, and it’s the same.

Realizing my high school group chat—the one with my closest friends, the one that used to buzz every day—has gone quieter. Or when Snapchat shows me a memory from this exact day, a year or two ago—me in the same city, on the same street—but I barely recognize the version of myself looking back.

I see a kid staying out too late for no reason, drunk on cheap beer, saying things just to fill the silence, convinced we were all going to stay the same forever. The same buildings, the same sidewalks, but everything feels tilted, a little off. Like the person in the photo hadn’t realized yet that they’d already crossed over.

It never happens as I expect. I always think change will feel obvious, like some dramatic threshold I’ll consciously step over. But more often it feels like Spirited Away—like you’ve wandered into a place you can’t name, and by the time you realize you’ve crossed over, the road behind you is gone.

That’s what stayed with me, watching it again now. Chihiro doesn’t know she’s left her old world behind until it’s too late to turn around. Her parents are pigs, the sun’s gone down, and the rules don’t work the same anymore. The world looks familiar—an abandoned theme park, little storefronts, train tracks cutting through the trees—but everything’s tilted, eerie, just not quite right.

Growing up feels like that, sometimes. You move or start a new semester, or come home for the summer, and at first, it’s easy to pretend you’re still the same. But you’re not. You’ve crossed into something else. The rules have shifted. You’ve changed.

I think what unsettles me most isn’t the moment you step into the new space—it’s the moment you realize you’ve been there for a while. That you’ve already adapted. That somewhere along the line, you stopped noticing how unfamiliar it all felt.

College has been like that. The first semester was obvious—the nerves, the newness, the rituals of pretending to belong. But then somewhere along the way—I don’t even know when—the buildings stopped looking unfamiliar. The routines settled in. The new friends stopped feeling new.

Maybe it was the night we stayed up too late in someone’s room, or when we started texting just to send stupid memes, or when I realized I didn’t think twice about showing up unannounced. And by the time I noticed, I was already on the other side of it.

Chihiro standing alone in the amusement park

That’s what Spirited Away gets so quietly, so precisely right. Chihiro survives because she adapts—quickly, almost instinctively. She gets a job at the bathhouse. She learns the rules. She figures out how to make herself useful. But in doing that, she almost loses herself entirely. Her name—her real one—slips away.

And it’s only when someone reminds her who she is that she starts to find her way back. It’s not just about remembering her name—it’s about remembering that she has one, that she’s more than what the world around her needs or asks from her. That under the job, the tasks, the role she’s playing to survive, there’s still a person who belongs to herself.

That part feels familiar, too. I adapt—to a school, a city, a relationship—and somewhere along the way, I lose track of the person I was when I arrived. Not all at once. Quietly. One day I look up and realize I’ve gone a little blurry around the edges.

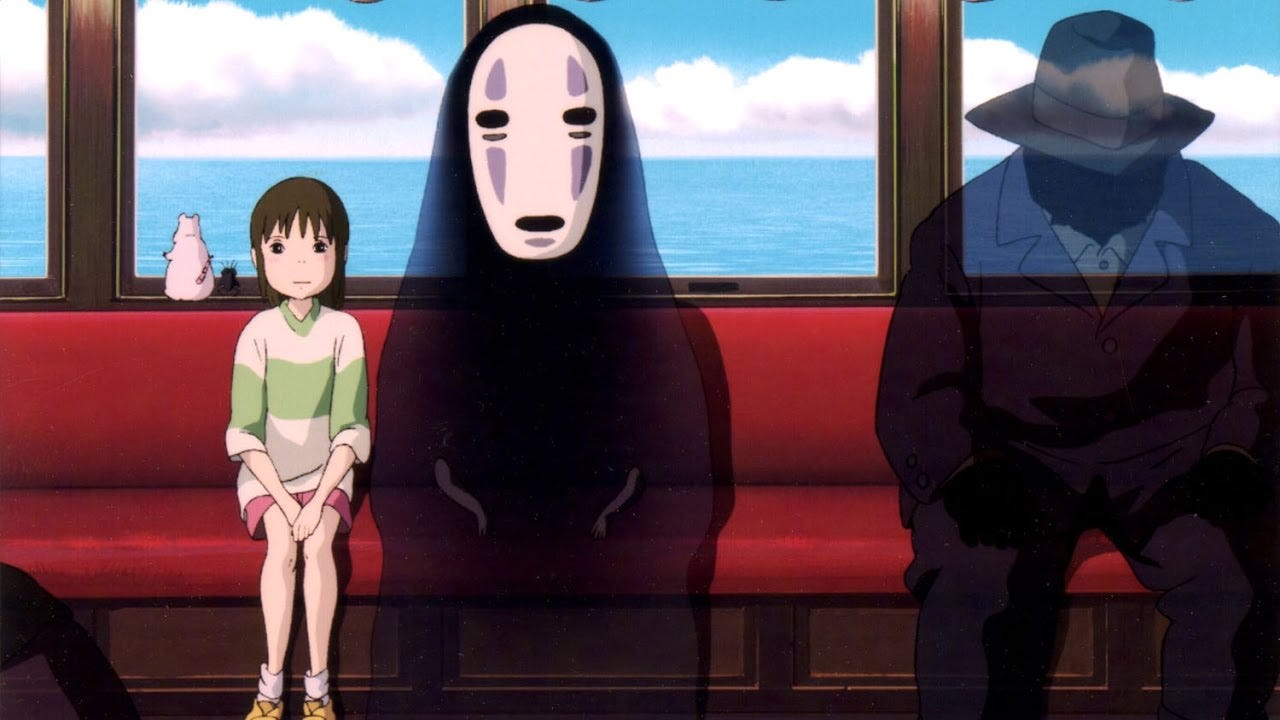

There’s a scene in Spirited Away—maybe the most haunting one—where Chihiro boards a train that glides silently over flooded tracks, stretching out across the water with no clear end in sight. The train doesn’t stop often. The passengers are quiet, faceless—not in the sense of missing features, but in the sense that they barely register, like shadows just passing through. The whole thing feels like moving forward, but with no real sense of where you’re going.

Chihiro, sitting on the train

That’s what growing up feels like. You get on, because what else can you do? The world shifts—new cities, new routines, people slipping in and out of your life—and by the time you realize how far you’ve gone, there’s no station to go back to. You just keep moving forward, a little older, a little more unsure, trying to remember the pieces of yourself you want to hold onto.

I think that’s what I didn’t understand the first time I watched the movie, as a kid. I thought it was about escape—about finding your way back. But it’s not, really. It’s about the way you change in the in-between spaces. The way you lose pieces of yourself to survive. And the quiet, steady work of trying to remember who you are—even when the world around you keeps shifting.

Maybe that’s the whole trick—not avoiding the thresholds, but noticing them. Catching yourself in the middle of the shift, even if it’s already happened. Realizing the old version of you isn’t fully here anymore, but you’re not entirely sure who’s replacing them yet.

I used to think growing up would feel like crossing a finish line—a moment, a decision, a scene you could point to and say, there, that’s when it changed. But it’s never that clean. It happens in small, forgettable ways.

You wake up one morning, and the city feels familiar. The apartment feels like yours. The people around you, the version of yourself you’ve settled into—it all feels solid until you look back and realize you crossed the threshold a long time ago. You just didn’t notice at the time.

It’s unsettling, but maybe also a relief. You don’t have to be ready. You don’t have to have it figured out. You just keep moving forward—through the flooded tracks, the in-between spaces—trying to remember your name.